Business Organizations / Groups

Guiding organizations to a more sustainable future

Today’s climate crisis urges us to rethink and reinvent our economy. Business needs to change to meet higher expectations of sustainability. Business groups should be well-equipped to guide organizations through this transition. Together we can make a real change, because sustainable business is the future.

The world is at a turning point and the decisions we make today will be felt by the generations that come after us. We believe a sustainable, prosperous future is within our collective reach. Business can join government and society by making strong commitments and transitioning toward sustainable practices. Together, we will make the impact that matters.

Governments, companies and individuals have to come together to address the urgent climate crisis. Policymakers, business leaders and the global workforce have a shared opportunity and responsibility.

Achieving our climate targets is a monumental task and it is going to take a whole-of-economy effort to make it happen. That means we need a transformation in the skills and jobs people have if we’re going to get there.

Green skills are the core of the green transition and harnessing the shift of talent. Through a targeted approach, we can progressively shift towards these greener jobs, using skills to identify jobs with the highest ability to turn sectors and countries green. We need more opportunities for those with green skills, we have to upskill workers who currently lack those skills, and we need to ensure green skills are hardwired.

|

Adapting to Evolving ESG Requirements |

|

In response to growing concerns among their employees customers, investors, and impacted communities, many firms are making themselves accountable for their environmental, social and governance (ESG) practices. How can businesses ensure future success by adopting the best ESG practices? |

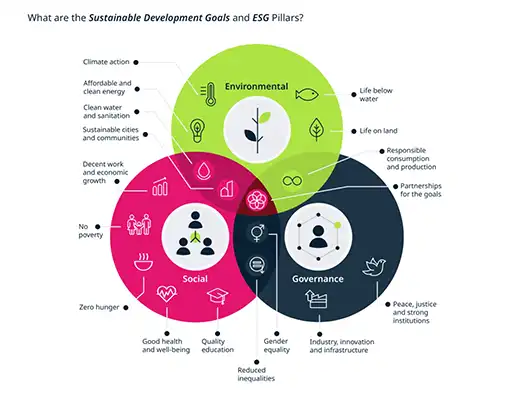

The ABC of ESG

ESG stands for Environmental, Social and Governance. Collectively, these cover a broad range of non-financial issues that are increasingly regarded as sources of both financial risk and opportunity. In this article, we’ll delve into the origins and implications of ESG.

The Origins and Growth of ESG

The original use of the term ESG dates back to 2004, when the then-United Nations Secretary-General Kofi Annan invited 55 CEOs of major financial institutions to participate in an international project to integrate ESG into capital markets. That group produced a study in 2005 entitled ‘Who Cares Wins’, which set out the business case for embedding ESG factors into investment decisions, thereby improving the sustainability of markets and leading to better outcomes for society.

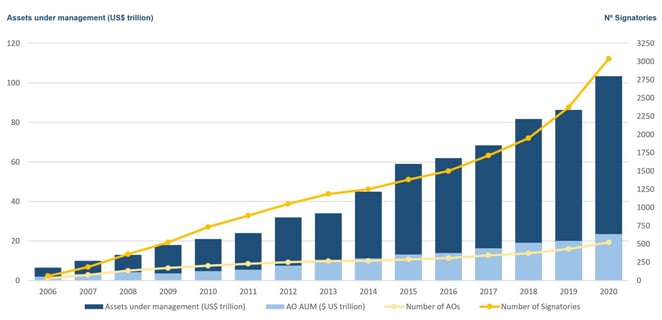

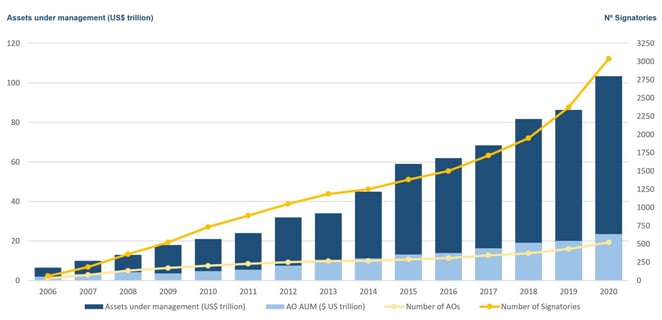

Since those early days, ESG investing has grown significantly. One indicator is the growth in the number of signatories and assets covered by the Principles for Responsible Investment Initiative (PRI) (Figure 1). Launched in 2006, signatories commit to incorporate ESG considerations into their businesses and investment processes.

Figure 1 PRI growth 2006 – 2020

Source: https://www.unpri.org/pri/about-the-pri

So What Counts as Being Part of ESG?

- The Environmental pillar refers to issues related to the natural world and includes aspects such as greenhouse gas (GHG) and non-GHG emissions; renewable/non-renewable energy generation and usage; biodiversity; land use; material resource use; water management and waste.

- The Social pillar refers to issues related to the lives of humans, such as human rights, modern slavery, child labor, working conditions, and employee relations.

- The Governance pillar captures the decision-making factors affecting a business, such as the gender and ethnic diversity of board composition, executive pay, bribery and corruption policies, political lobbying and donations, and tax strategy/transparency.

Where Does Climate Fit In?

The risks and opportunities from a changing climate most obviously fall in the environment pillar, although social (e.g. support for a ‘just’ transition to a low carbon economy) and governance issues (e.g. how well executive incentives align to climate outcomes) may also be relevant.

Investors’ Fiduciary Duties

An area of long-standing debate – particularly for asset managers – has been the extent to which taking account of ESG issues is compatible with their ‘fiduciary duty’, that is, the duty to work in the best interests of one’s clients. If fiduciary duty is interpreted as the maximization of shareholder value, it provides a reason to ignore broader environmental or social impacts, which might be costly to improve or rectify.

A UNEPFI sponsored report published in 2005 made it clear that there were no legal barriers in taking ESG considerations into account. Indeed, as they noted ‘…there is a body of credible evidence demonstrating that such considerations often have a role to play in the proper analysis of investment value’. While that report was helpful, it didn’t manage to end the debate and over the years this has been a constant refrain. Extensive work by the PRI and UNEP FI on this issue culminated in a 2015 report which stated that ‘Failing to consider long-term investment value drivers, which include environmental, social and governance issues, in investment practice is a failure of fiduciary duty.’ (Emphasis added).

Beyond Asset Management

ESG issues are not just pertinent to asset management and asset owners. Initiatives similar to the PRI have been launched more recently for Insurance and Banking. The spirit of all these initiatives is that ESG issues need to be considered as potential sources of risk as they can impact a firm at any point.

Indeed, today’s 24-hour news cycles and social media make the reputational impacts of ESG transgressions particularly difficult to manage.

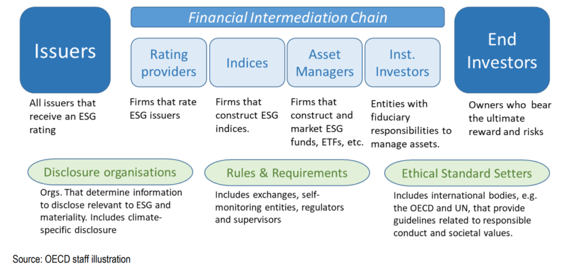

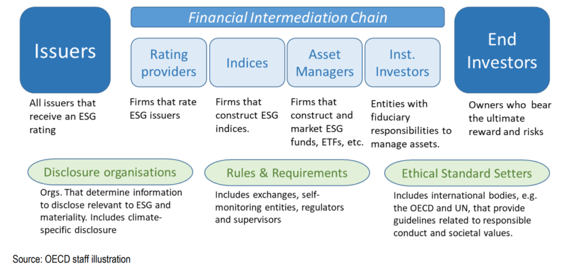

ESG Fragmentation

That said, judging which ESG issues are financially relevant and material for a particular firm can be difficult. Because ESG data and metrics have not traditionally been part of the mandatory financial reporting frameworks, a plethora of different approaches have grown up, making it challenging to compare across firms. And although there are efforts to introduce a globally more consistent approach to sustainability reporting, the landscape at the moment is confusing and fragmented. Indeed, as a 2020 OECD report noted, there is now an entire ESG financial ecosystem, from issuers to end investors, ratings providers, firms that construct ESG indices, standard setters, and disclosure organizations, and they could all be using different definitions and metrics (Figure 2).

Figure 2 ESG financial ecosystem

Source: https://www.oecd.org/finance/ESG-Investing-Practices-Progress-Challenges.pdf

Work is underway by the five leading framework and standard-setting organizations – CDP, Climate Disclosure Standards Board (CDSB), Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC) and the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) – to work towards a comprehensive corporate reporting system that includes both financial accounting and sustainability disclosures as outlined in their shared visiondocument in September 2020. But that will take time.

In the meanwhile, care is needed. Self-reported ESG metrics by firms will tend to put a gloss on issues of interest from a risk perspective. ESG ‘scores’ of companies from different providers are not well correlated, reflecting differences in proprietary methodologies, weighting schemes, and materiality assessments. Indeed, it is questionable if it even makes sense to weigh together the differing aspects of the three E, S, and G pillars to get to an aggregate score. (For an interesting discussion on this and other topics, listen to a recent GARP Climate risk podcast).

But even if you restrict yourself to just looking at the Environmental pillar, a recent OECD report highlights how little alignment there is between E scores from key rating providers (Bloomberg, MSCI, and Thomson Reuters) and climate risk indicators such as carbon dioxide emissions, and waste and water metrics. As they put it, “the E of ESG investing – in its current form – may not be the most effective tool for investors who wish to use it to align portfolios with climate transition to low-carbon economies”. Definitely food for thought for anyone wanting to use ESG scores as a shortcut to investing in climate-friendly investments.

Environment, Social Governance (ESG) – A Global Issue

Companies are expanding the metrics they use to define success well beyond profit and sales. In response to growing concerns among their employees, customers, investors, and impacted communities, many firms are making themselves accountable for their Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) practices. Mainstream investors once considered such measures “non-financial,” but have come to understand both related risks and opportunities – and are demanding more related data. The amount of ESG information being made available by rating agencies, technology firms, and auditing and consulting firms has exploded as a result, and efforts are afoot to bring more coherence and consistency to it through standards and regulation.

ESG Regulation and Policy Making

Without proper Environmental, Social and Governance regulation potentially harmful ‘greenwashing’ efforts may flourish

The market for sustainable investing has expanded rapidly. Both financial and non-financial firms have begun making claims about the environmental and social performance of the investments they offer, in hopes of tapping into a growing trend. For non-financial firms like technology companies their claims may take the form of sustainability reports designed to attract certain equity and debt investors, while financial firms have developed product labels like “green bond” and “sustainable growth fund” with the same goal in mind. If left unregulated, however, the potential for rampant “greenwashing” presents a serious challenge for the ESG capital market. Firms and financial actors have an incentive to make their activities appear green, without going to the trouble of carefully measuring, auditing, and improving actual ESG performance. If greenwashing firms are rewarded by the unsuspecting, it could further exacerbate bad behaviour. And, when deceptions inevitably come to light, the resulting decline in trust could cut general demand for ESG performance, erode the incentives for good behaviour, and even collapse the overall market. To be sustainable, the ESG-informed capital market therefore needs more ways to reliably and systematically validate ESG claims.

This validation can be derived from industry self-monitoring and auditing, non-governmental organizations, government regulation, or technologies like blockchain. The first significant efforts to regulate ESG were made through non-governmental organizations like the Global Reporting Initiative, the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board, and the Financial Stability Board’s Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures, which define standards for the reporting of non-financial ESG information. The issue with such voluntary standards, however, is adverse selection – only certain firms have an incentive to accurately report and audit, while others are content to avoid scrutiny. In 2020, governmental regulations began to develop that fully cover the market, like the EU taxonomy to define and oversee differing levels of rigour in the ESG investing market. The US Securities and Exchange Commission has also considered required disclosures. The need for convergence among non-governmental and governmental standards has pointed to the importance of harmonizing institutions like the World Economic Forum’s Stakeholder Capitalism Metrics Initiative, The Value Reporting Foundation, and the Impact Management Project. Perhaps the most important of these is the International Sustainability Standards Board, created by the International Financial Reporting Standards Foundation and launched at the COP26 climate summit in Glasgow. This new entity is the result of a merger between the Climate Disclosure Standards Board and the Value Reporting Foundation, which houses the Integrated Reporting Framework and the SASB Standards.

ESG Investment Integration

Portfolios may outperform by tilting towards companies with high Environmental, Social and Governance scores

ESG investment integration means using Environmental, Social and Governance performance data to construct a portfolio – to both maximize returns and address ethical concerns. Asset managers are increasingly purchasing data from ESG rating agencies and integrating that with other available corporate information to guide investment decisions. From an ethical investing perspective, ESG information enables a finer-grained approach than simply screening out industries like weapons, addictive substances, fossil fuels, or private prisons. By using ESG data, for example, it is possible to invest in fossil fuels using a “best in class” approach that excludes companies above a certain level of carbon intensity, or to only own tobacco companies with responsible marketing practices. Unfortunately, this exclusionary approach to publicly-traded equities has had only weak and indirect impacts on firm behaviour. ESG integration may therefore fit best within a “virtue ethics” perspective, where investors refuse to benefit from things they don’t believe in. One alternative is to take a “consequentialist ethics,” or impact perspective – where investors use their money to try to change the world for the better. However, to have that kind of influence on corporate behaviour, it will likely require active and engaged ownership.

The primary benefit of ESG integration may be financial – at least, in situations where ESG variables are predictive of future financial performance. While scandals related to harsh labour conditions in supply chains, corruption schemes, and environmental damage can affect a company’s reputation and stock price, they may also be anticipated by low ESG scores. Meanwhile a company’s greenhouse gas emissions may point to future costs, as governments increasingly move to put a price on carbon. In aggregate, ESG appears to have a neutral-to-positive impact on financial performance; as a result, it may be possible for portfolios to outperform by tilting towards companies with higher ESG scores. This has driven a meteoric rise in ESG investing, though there are two main issues that may impede further progress. The first is the high level of noise within ESG data, which tends to reduce its correlation to financial performance (though new techniques to address this might strengthen the signal). The second is the added capability needed within investment firms, given the complexities of ESG data and the variety of values and preferences among clients. Building related capacity will likely require the joint efforts of academia and industry.

ESG Ratings and Rankings

Useful Environmental, Social and Governance performance measurement relies on a shared definition of ESG

Due to the sheer abundance of ESG information about companies now being made available, investors and other stakeholders need distilled, actionable data – such as ratings or rankings. ESG ratings compress a variety of data points into a single score, or small set of scores, while rankings use performance to slot firms into an order. When stock or securitized debt in multiple companies is included in an investment fund, it is possible to combine the companies’ collective ESG ratings to create ratings and rankings of different funds. The most common producers of ESG ratings and rankings are agencies like MSCI or Morningstar’s Sustainalytics, and media publications like the Newsweek Green Rankings or Corporate Knights. Index providers, asset managers, and even asset owners are increasingly constructing their own proprietary rating and ranking schemes. However, these generally present three major issues: the “aggregate confusion” problem of rating divergence, value tradeoffs, and transparency. The aggregate confusion problem is most visible, because of the significant divergence between ESG rating agencies. For example, one MIT study found only a 46% correlation between the two most prominent agencies, MSCI and Sustainalytics.

This divergence means investors may have difficulty trusting ESG ratings, and one of its main causes is disagreement about how exactly to define ESG – one agency might include electromagnetic pollution, for example, while another includes lobbying, though both may agree on carbon emissions. Agencies may also disagree on measurement techniques. One firm might measure women’s empowerment as the number of female board members, while another uses the number of sexual-harassment lawsuits filed. The value tradeoffs problem occurs because almost all ratings are constructed using weighted linear averages – so a firm can decrease ESG performance in one domain, increase it in another, and maintain the same rating. ESG rating schemes rarely disclose the weighting assigned to different factors, or incorporate investor preferences. This points to the third issue: transparency. Because rating agency business models involve selling proprietary datasets to investors, they have an inherent interest in maintaining strict control of that data. However, this lack of transparency makes it difficult for investors to properly interpret or use ratings and rankings – making appropriate oversight of rating agencies to ensure transparency a prominent topic in discussions about ESG regulation.

ESG Data Collection

The hunt is on for more independent sources of information about Environmental, Social and Governance performance

Given the obstacles presented by the coverage, comparability, and reliability of companies’ self-reporting on their own Environmental, Social and Governance performance, investors and other stakeholders are beginning to seek out more alternative and independent sources of information. This in turn is driving greater innovation when it comes to ESG data collection and analytics. The first category of this data derives from advances in physical sensors – which power the Internet of Things, satellite imagery, and remote sensing capability more generally. For example, satellite images of flaring at oil and gas company operations can be used to detect and ultimately eliminate this wasteful and polluting phenomenon, which is a prominent source of greenhouse gas emissions. Meanwhile newer satellites equipped with high-resolution imaging technology can be used to detect concentrated sources of methane emissions from livestock – a not-insignificant cause of harmful global warming – and problematic areas of fossil fuel extraction. And, small robotic sensors can be deployed to patrol sewage systems near corporate facilities, and identify disease outbreaks or even opioid use among employees.

The second category of ESG information results from advances in information and communications technology platforms such as e-government and social media sites. Scraping information from publicly-available government databases can help track down filed lawsuits, workplace injuries, reports of environmental pollution and other indicators of ESG risk. Meanwhile social media services like Twitter, LinkedIn, and Glassdoor (as well as blogs and traditional news sources) are available for data scraping and natural language processing that can identify the prevailing sentiment about firms among current, prospective and former employees, customers, and investors. While it is not a source of information per se, the analytics that become possible when combining organic data sources like those mentioned here with self-reported information from firms can be invaluable. Machine learning algorithms may be able to identify and predict ESG risks using an array of physical, social media-based, and reported data with greater reliability than any single data source. This can help investors and other stakeholders maximize the benefit of available ESG information, and identify the social and environmental hazards most likely to occur.

ESG Shareholder engagement

Environmental, Social and Governance-based engagement can help drive climate action and address public health issues

In addition to shaping their portfolios through ESG integration, investors may choose to actively drive related improvements at companies through greater shareholder engagement. Evidence suggests this is a far more effective way of shaping corporate behaviour than simply buying and selling stock. The ways in which investors can approach this depends on asset class, however. Private equity investors, for example, are likely to have relatively large ownership stakes and therefore more direct access to management teams (large PE funds like KKR and TPG regularly engage with senior and middle managers, as well as front line workers, to identify ESG issues and encourage development of related strategies, measurement, disclosures, and operational practices). For buyers of public equities, the style of engagement depends on their scale and objectives. Large asset managers with long-term investment styles are likely to have greater and more prolonged access to management teams, similar to what is afforded to private equity backers. Meanwhile activist hedge funds tend to take large stakes in firms for short periods of time, through leveraged capital and borrowing – and then use that time to mount aggressive campaigns.

Examples of ESG-centred shareholder engagement include Aviva Investors’ push for Apple to address youth smartphone addiction, and Engine No. 1’s campaign to drive stronger climate action at Exxon Mobil by replacing board members. Smaller, socially-responsible asset management firms like Boston Trust Walden, and values-based asset owners like religious pension funds, often engage firms by initiating shareholder proxy votes that call for stronger ESG strategies. Individual retail investors can join campaigns mounted by larger activists, though most delegate their voting power to index fund managers like BlackRock or Vanguard (which tend to follow shareholder voting guidance from firms like ISS and Glass Lewis). ESG shareholder action tends to focus on three objectives: disclosure, target setting, and governance. Disclosure, the most common, relates to the frequency of, quality of, and auditor assurances behind ESG information. Target setting can occur once ESG data is made available, and can be used to improve things like greenhouse gas emissions. In terms of governance, investors may simply ask for more rigour from a firm – both for its own sake, and as an enabler of the greater good through instruments like aligning executive compensation with sustainability goals.

ESG Skills and capabilities

The employees required to assess new layers of corporate performance need a blend of competencies and skills

As the Environmental, Social and Governance marketplace grows, every firm involved is in need of people equipped with up-to-date sustainable business and investment skills. Banks and asset managers have been staffing up their ESG departments to help them analyse the non-financial performance of firms, and integrate that information with more traditional financial data in order to more comprehensively inform their investment decisions. Entirely new financial firms are also emerging, to supply the market with sustainable investment products like green bonds and access to activist shareholder funds and clean technology-focused venture capital investments. Their employees need a combination of foundational financial analysis skills and fluency in the language of carbon emissions, living wages, political activity, and other ESG matters – as well as an ability to critically consume related information. Non-financial firms need sustainability departments capable of measuring and monitoring firm performance, and communicating in an accurate and timely way to the capital markets and other stakeholders. The necessary related skillsets include an ability to engage and collaborate with business leaders while bringing a broader set of stakeholder concerns to the table.

To better connect businesses and disparate stakeholders, there is a growing industry of data providers, analytics and artificial intelligence firms, rating agencies, and other services designed to help process new layers of information about corporate performance. The necessary skillsets for this combine data analytics, computer science, and consulting with a deep understanding of sustainability. To develop a new generation of professionals equipped with these skills, business schools can further integrate sustainability into their curricula, and collaborate with operational and financial disciplines. Meanwhile academic programs in the environmental and social sciences can prepare people to apply their expertise to capital markets. Professional associations of investors, auditors, and accountants can provide continuing ESG education via organizations like the CFA Institute. Because ESG skills are often hybrid, the necessary certification and credentialing has been idiosyncratic – MBAs and Master of Finance degrees appear in credentials alongside degrees in environmental science or labour economics. While some people may have dual degrees covering such fields, others pursue specific sustainability certificates. As the ESG field matures and solidifies, employers may begin to seek more such harmonized certifications and credentials.

ESG Reporting comparability and assurance

Environmental, Social and Governance reporting occurs too infrequently to keep up with evolving expectations

Corporate sustainability reporting has become common practice for large firms, and is the most widely used source of information about ESG performance. A KPMG survey in 2020 found that among 5,200 top-earning firms in 100 different countries, 80% were doing sustainability reporting – which rises to 96% for the world’s 250 largest firms. However, generating sustainability reports can be labour-intensive and costly. The internal data collection necessary often requires dedicated staff and consultants, making it prohibitive for smaller firms. Even firms that do report on ESG factors only do so on an annual basis, even as quarterly reporting of financial results remains the norm. This lower frequency ESG reporting may be insufficient to keep up with rapidly increasing social and regulatory expectations on matters like greenhouse gas emissions. Another issue stems from the varying definitions of and expectations for ESG and sustainability. A firm may decide an issue is not worth disclosing, though investors and other stakeholders might disagree. As a result, if the only source of ESG data is corporate reporting, markets may not be able to react to some critical issues and stakeholders may seek out greater innovation in related data collection.

Another challenge is related to inconsistencies in data pulled from corporate reports, due to the different ways firms measure and reflect ESG factors. For example, firms might count greenhouse gas emissions only from their direct operations, or more comprehensively from their supply chains; those that are more rigorous and inclusive in their measurement might appear to be doing worse than those reporting in a more cursory way. For this reason, standards have been essential for the development of ESG reporting – such as the GHG Protocol, CDP, GRI, SASB, and the newly established International Sustainability Standards Board under the IFRS Foundation. There is also the issue of reliability and trustworthiness, given the incentive firms have to indulge in greenwashing that makes their operations appear less risky and more virtuous. One key related development has been an increase in the auditing and assurance of corporate sustainability reporting. The KPMG survey found that 2020 was the first year in which a majority of large firms had invested in the independent assurance of sustainability reports (51% of the 5,200 top firms in 100 in countries, and 71% of the world’s 250 largest). As regulatory requirements for ESG reporting increase, these figures are also likely to increase.

Using ESG to measure success

Environmental, Social and Governance performance is not captured in quarterly earnings reports

At its root, ESG is about expanding our appreciation of a firm’s performance and impact. While quarterly earnings reports might convey key figures, they leave much hidden related to both the causes and effects of the firm’s success. By widening our view, we may see that a mining firm’s profits come at the expense of workers, communities, and the environment, for example – while another firm in the same industry may be investing in worker safety and environmental efforts in ways that aid long-term performance, but do not show up in a balance sheet. This wider view helps determine whether firms can be considered “sustainable,” and so it is essential to enable broad access to it. While firms can constrain their own future success if they negatively impact the people, customer and community trust, or natural resources they depend upon, one key challenge relates to how broad the view of these impacts and risks should be. What should be in scope when assessing “non-financial performance” for technology firms, relative to automotive companies, mining interests, or financial firms? And, how long should our time horizon be when considering related risks and impacts?

There are no easy answers to these questions, and different countries and institutions define sustainability differently. ESG has become an umbrella concept for hundreds of issues, practices, and metrics used to hold firms accountable. One MIT study of ESG rating agencies found that 50% of the significant divergence in ratings was caused by differences in scope and definition. The World Economic Forum and its partners have sought to lessen these differences by developing the “Stakeholder Capitalism Metrics,” designed to make ESG metrics comparable across industries and regions; more than 170 companies have so far adopted them and more than 70 have reported against them. Writing and publishing reports may increase transparency, but it does not change practices. And while buying and selling equities based on ESG information is increasingly common, the effects on firms (and society in general) are indirect at best. ESG information can only improve the world under certain conditions: when C-suite executives actually use it to guide decision making, when it attracts the best employees, customers, suppliers, and capital, when it influences regulatory action, or when it impacts shareholder voting – which can make non-financial information truly material.

Improve your ESG performance and generate quantified triple bottom line results: People, Planet, Profit

A good sustainability strategy goes beyond ESG reporting. Identify the relevant ESG metrics, build a solid monitoring system and establish a governancefrom which corporate leaders can make sound strategic decisions. We progress alongside your company as your ESG partneras you evolve on your sustainability journey. With the right strategy in place, you will improve your ESG performance and reap the positive TBL results generated on People, Planet, Profit.

Questions to help you answer:

- What ESG metrics are relevant to my business and industry?

- How do we measure and keep track of ESG metrics while ensuring engagement and ownership at all levels of our organization?

- We want to improve on our ESG performance, which initiatives can help move the needle?

Next Generation ESG

Young people believe companies should be held accountable for their environmental, social and governance standards

The COVID-19 pandemic has spawned a new generation of organized young voters, consumers, and investors who are eager to rally behind issues like climate action and social justice. This generation poses an existential threat to those institutions that seek to simply revert to business as usual post-pandemic – but they also represent a massive opportunity for other businesses (and governments) in search of a progressive mandate. The Davos Lab Youth Recovery Plan report published in 2021 reflects survey responses from millions of mostly young people, and dozens of related dialogue sessions – and points to a broad agreement that more inclusive, responsible business practices are essential. More than half of the respondents “strongly” agree with the idea that all private-sector organizations should be held accountable for their environmental, social and governance (ESG) standards of ethics (in addition to their technology standards of ethics) – and less than 2% disagree with this idea. When asked about the most prominent barriers that stand in the way of implementing more responsible business practices, the most popular response was, “It is less profitable to do so.”

However, young people believe companies that seek to embrace technology ethics through transparent and inclusive operations can differentiate themselves from competitors – and draw in greater amounts of revenue and users as a result. Establishing effective governance frameworks and implementing a true stakeholder capitalism model (meaning a model that is focused on far more than just the bottom line) in order to mitigate the risk of technology-related ethical lapses and misuse are more important than ever. When young survey respondents and dialogue session participants were asked what big idea can be put forward to help make next-generation ESG a reality, and genuinely impact the way corporations do business, they recommended compiling global best practices and proven, effective regulations. These can then be pooled into a robust knowledge base and disseminated to the incubators, accelerator programs, and private equity firms that are tasked with forming, guiding, and investing in the next generation of companies. Meanwhile as universities develop the next generation of leaders, according to the Youth Recovery Plan report, they should ensure that ESG literacy and an understanding of ethics are central to their business- and technology-related instruction.

What is ESG? Everything You Need to Know About Environmental, Social, and Governance

Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) considerations are shifting the strategic focus of businesses worldwide. Today, ESG principles guide decision-making processes, from high-level strategy to day-to-day operations, fundamentally changing the way we understand success and value creation.

This approach promotes a systemic view of the business ecosystem, highlighting the interconnectedness of operations, environment, and society. It motivates companies to innovate, redesigning their processes and products to minimize their environmental footprint. This strategic shift doesn’t only reduce costs, but also future-proofs the business against escalating environmental risks and regulations.

ESG principles are fueling the innovation engine of businesses, pushing them beyond their conventional boundaries. The need for sustainable solutions has turned challenges into opportunities, transforming businesses into crucibles of creativity. The result is a new wave of products and services that meet the needs of a growing segment of conscious consumers, enhancing market share and boosting revenues.

The integration of ESG principles is a strategic game-changer. It catalyzes efficiency, spurs innovation, enhances brand value, fosters a resilient corporate culture, and attracts investment. The strategic embrace of ESG is not just about doing good—it’s about doing well by being good, balancing profitability with the needs of the planet and its people.

ESG management software: Maximise efficiency and business success through automation

|

|

|

|

Given the growing importance of ESG factors in business success, ESG management and reporting software plays a crucial role in today’s corporate landscape. Automated solutions offer clear advantages in terms of efficiency, accuracy and transparency. ESG software can streamline data collection, analysis, and reporting, saving time, costs and resources, while reducing errors. In contrast, manual approaches are labour-intensive and prone to errors, and can quickly become outdated. One needs to know about ESG management and reporting software, covering such topics as:

|

Does ESG reporting really move the needle in fighting climate change?

5 practical tips for improving ESG reports

Final adoption of ESRS a ‘game changer’ for mandatory reporting

Read more….

1.5°C BUSINESS PLAYBOOK

Why 2024 is the year sustainability develops a credible business case

ESG METRICS GUIDE FROM NOVARTIS and ISOMETRIX

Read more….

SCIENCE-BASED TARGETS for NATURE And Business

High-level Business Actions on Nature

FOUR ACTIONS FINANCE TEAMS CAN TAKE ON NATURE

A Guide to Addressing Scope 3 Value Chain Emissions

Climate Action Game Changers: Carbon Markets

7 sustainable finance challenges to fix global inequality

Social Impact Reporting

SDG Playbook for SMEs

ESG Playbook – The complete sustainability reporting platform

What every company needs to know about climate risk assessment

Read more….

Transition Plan Taskforce

Innovation

Innovation is the process of turning new ideas into value, in the form of products, services, business models, and other new ways of doing things. It is complex and goes beyond mere creativity and invention to include the practical steps necessary for facilitating adoption. New developments tend to build on earlier versions, in a way that fuels productivity and economic growth. It is now clear that truly innovative firms can have significant impacts on business and society as a whole while outperforming their peers in a number of ways.

Business model Innovation

Developing new business models can rewrite the rules of an industry

The internet spawned Airbnb, Amazon, Netflix, Uber and many other companies that have used business model innovation to rewrite the rules of their industry. That means they managed to change accepted ways of doing business, challenged the status quo, and served new customer needs while meeting existing needs in new ways. In doing so, they created enormous wealth for shareholders while providing useful services for customers. They have also been sources of inspiration for more established firms like Bosch, IKEA, or Philips as they assess and update their own business models. To better understand business model innovation, it helps to define what a business model is. As noted in the 2021 book Business Model Innovation Strategy, these core elements characterize a business model: what, how, who and why. More specifically, what activities does a business model encompass; how are these activities linked (for example, in terms of sequencing or exchange mechanisms), who performs the activities (which are performed by the focal firm versus those performed by partners, suppliers, or customers), and lastly why does the business model create value and enhance value appropriation for the focal firm?

Firms can innovate the “what” by adding or eliminating activities (for example, when Apple began selling and distributing content for electronic devices in addition to designing and manufacturing those devices). They can innovate the “how” by linking activities in new ways (Netflix first competed against video-rental stores through postal distribution, then via online streaming). Firms can also innovate the “who” by changing who performs certain activities (Tesla performs the sales function in-house instead of outsourcing it to dealers). Lastly, firms can innovate the “why” by adopting new revenue models and value logic (for example, Dropbox makes basic file storage free but charges for additional capacity). Much business model innovation has been driven by advanced information and communication technologies that enable new ways of doing business, though it is distinct from technology and product innovation. Business model innovation often flows from a unique take on customer needs and the best ways to satisfy them. The idea of software-as-a-service, for example, represented by firms like Salesforce, was driven by a realization that customers do not necessarily care about owning software outright. Such business model innovation can be a powerful source of competitive advantage, though it requires astute implementation and simultaneous change in multiple parts of the organization.

Innovation and Ecosystem

Governments can help innovators avoid the so-called ‘Valley of Death’

“Government” may not be the first thing that comes to mind when thinking about innovation. Yet, together with academia and industry, it is a key pillar of the innovation ecosystem necessary to foster economic and social development. Some of the greatest innovations – such as spaceflight and the internet – have been made possible through government support and resources including financing and the testing environments needed to scale up impactful ideas. Governments themselves are constantly in need of greater innovation, in areas like drones for delivering medical supplies, sustainable urban farming, and digital twins for smart-city infrastructure – and there is untapped potential in many regions. For example, Europe is home to a wealth of research done at universities and in companies and governments. Max Planck Gesellschaft, Centre national de la recherche scientifique, and the University of Oxford are just some of the global leaders in the region, yet more can be done in terms of commercializing their discoveries. It is worth noting that it has been estimated that nearly 95% of the existing patents in Europe are inactive.

Among the reasons for this: private investors tend to be unwilling to fund research projects, which are usually characterized by high risk and complexity, significant expenses, and long gestation periods. As a result, researchers often lack the resources required to locate and validate the right market to commercialize their discoveries – an innovation gap sometimes referred to as Europe’s “Valley of Death.” Keeping in mind that Europe’s active patents, or just 5% of the total, contribute to more than 40% of the region’s GDP (according to the European Patent Office), is there a way to improve the process of commercializing discoveries? According to a European Commission study, three lines of related work have been explored. The first is tailoring co-investment mechanisms for early-stage ventures (such as proof-of-concept projects), while grouping together corporations and private investors interested in science-based startups and bolstering philanthropic funds (including those focused on impact investing). The second is tailoring existing investment mechanisms for technology transfer, while validating related policies via small experiments (sandboxes). The third is better supporting technology-transfer while aligning regulatory frameworks to simplify nation-wide scaling for startups.

Technology Innovation

The promise of emerging technologies is matched by a need to manage related uncertainty

Emerging technologies like quantum computing, augmented reality, and gene editing tools present many opportunities. At the same time, they are the cause of immense uncertainty. Some particular sources of that uncertainty include the market applications a new technology will serve, the users who will adopt it, the related activities that will support its expansion; and the business models that will be deployed to commercialize it. A holistic approach can help managers unbundle specific sources of uncertainty and the potential interaction among them, according to an article published in Strategy Science in 2021. For example, quantum computing has made several exciting technological advances, yet it can still be difficult to predict how it will evolve and create genuine value. Several questions remain regarding the technology, including at what point it can consistently and reliably outperform existing high-performance computing solutions. While some early-stage approaches have utilized “quantum annealing” technology – which is an alternative method of quantum computing that is already becoming commercially available – the next generation of the technology, dubbed universal gate-based quantum computing, is not expected to become widely-scaled-up for several years.

In terms of specific applications, quantum computing can serve many industries. Possible use cases include finance (for trading and risk management) and logistics (scheduling and planning), and eventually pharmaceuticals (drug development), security (encryption), and more. Still, there may be uncertainty about how various actors will contribute to the technology’s value proposition; quantum computing does not necessarily hold utility when used simply to solve current problems faster than existing solutions, so to realize its full potential reformulating old questions or raising new ones is needed (companies such as 1Qbit, which specializes in “recasting” questions and problems related to quantum computing, have grown in value). Cloud-based ventures, including those focused on data storage, will also be important for bringing quantum technology to commercial fruition. Ultimately, it will require a business model – though that is difficult to design when the technology is still rapidly evolving, and use cases are still not fully defined. It will likely be several years before its true potential becomes clear. Meanwhile governments via initiatives like the Barcelona Supercomputing Center (and its spin-off Qilimanjaro) and companies like IBM have been shouldering substantial related upfront investments.

Social Innovation

Profit is not the only source of inspiration for innovators

Examples of social innovation are all around us; they include everything from kindergartens and hospices to Wikipedia, Kahn Academy, and microfinance (small loans made to entrepreneurs in the developing world who do not have access to traditional financing). Social innovation is often defined as innovation that aims to tackle both social problems and the means used to address those problems. This can take the form of new products, services, initiatives, business models, or simply novel approaches to accessing public goods – often achieved by creatively re-combining already-existing elements. The field has developed rapidly in recent years, according to a 2022 report published by the Academy of Management, as new sources of funding, public policies, academic research, and networks emerge. The everyday work of social innovation typically happens within social enterprises (organizations working to solve social problems using market-based approaches), charities, non-governmental organizations, social movements, or patient groups. Universities, large companies, and governments also play roles, particularly in terms of validating ideas; results have included the construction of public playgrounds and the commercialization of community-developed, open-source software.

One notable development in the realm of social innovation is the deployment of pay-as-you-go (PAYG) technology. This enables companies to cater to people living in relative poverty, by accepting small individual payments for key services. As with prepaid phone services, customers can buy small and therefore more affordable amounts of credit. Solar energy companies like Angaza and affordable water organizations like eWater Services use PAYG technology to reach customers that might otherwise be denied such services. However, a lack of immediate commercial incentives can make it difficult to raise the capital needed to support such social innovation. As a result, organizations continue to experiment with frugal innovation – to make potentially scarce resources stretch further. One example of this is the M-Pesa mobile phone-based payment and micro-financing service, which has been deployed in countries in Africa, Asia, and Europe to facilitate banking services without requiring access to an actual bank. Due to their limited funding, social enterprises often adopt hybrid for-profit and non-profit legal structures – enabling organizations like Sanergy in Africa to supplement revenue with philanthropic donations.

Open Innovation

Many talk about corporate venturing, relatively few know how to successfully implement it

Established companies innovating together with startups, often called “corporate venturing” or “CV,” is a fast-growing phenomenon that takes many forms. These include corporate venture capital, corporate accelerators, venture clients, venture builders, and joint proofs of concept, to name a few. Since 2016, corporate venture capital investment has increased four-fold globally; this is a part of open innovation, a growing paradigm that assumes firms can and should use external ideas and paths to market as they look to advance their technology. These external inputs may come from startups, governments, universities, venture capital investors, or accelerator programs. The South Korean multinational Samsung, for example, gained a foothold in next-generation quantum computers by directly investing in the startup IonQ, which later went public, and German athletic apparel company Adidas partnered with the California-based startup Carbon to develop a 3D-printed shoe. On average, nearly 69% of corporate-startup innovations fail, however, according to a report published in MIT Sloan Management Review. So, what is the remaining roughly 31% doing differently? What is the right structure, degree of autonomy, and sources of deal-flow for the teams running corporate venturing and startups, for example?

Some popular myths include the notion that corporate venturing is only for large corporations (many small- and medium-sized enterprises are pursuing it), and that it is just corporate venture capital (it encompasses other mechanisms such as the “venture client,” where the corporation is the first client of the startup). Some also mistakenly think CV is just about intuition; abundant data are available to drive it forward strategically. Looking ahead, there are two predominant trends. The first is a growing number of corporations innovating with deep-tech startups, or those with emerging technologies based on scientific discoveries and offering a substantial advance over established technologies (illustrated by the expansion of the American chipmaker Intel’s deep-tech startup accelerator Ignite). The second is a growing number of corporations forming small groups to innovate with startups – so called “CV squads” – to share costs, anticipate opportunities, and strengthen value propositions. The carmaker Volvo, for example, did this by teaming up with telecommunications firm Ericsson and others. To capture the true value of corporate venturing, in terms of fielding innovative new products and services, chief innovation officers should make a point of reviewing their existing CV strategies.

The Digital Transformation of Business

COVID-19 catapulted businesses everywhere into the digital-first world. Technology had already been reshaping industries, business models, supply chains when the pandemic hit – as people demanded more touchless and online experiences. Yet, the results have so far been mixed, and many businesses have fallen short of their digital transformation goals. Those businesses slow to change – particularly small firms – have become especially vulnerable to disruption by digital natives. The technology decisions made by the leaders of these and other companies now will help determine not only their own future success, but also the success of their employees, customers, and partners.

New Digital Business Model

Technology-enabled models can help companies provide value and build resilience

Most executives see innovation as critical for their business. And, according to the McKinsey Global Innovation Survey, 80% think their current business models are at risk of disruption. COVID-19 has only accelerated the shift to online and touchless experiences, and spurred innovative uses of technology and data that will increasingly underpin business models. Digital subscription models, like Dollar Shave Club or Netflix, have already risen to prominence, as have on demand models like Uber or TaskRabbit – while technology has made it increasingly easy to adopt platform models upon which users and even other companies can build their own presence (examples include Facebook or YouTube). The World Economic Forum estimates that 70% of the value created over the coming decade will be based on digitally-enabled platform business models, due to the rapid digitalization of economies around the world. Collaboration can also unlock value – research shows that digital “ecosystems” are expected to account for more than 30% of global corporate revenue by 2025. One example is Project Connected Home, a joint effort led by Amazon, Apple, Google and the Zigbee Alliance to set standards for smart home technology.

“As-a-service” business models are an increasingly prevalent and effective way for companies to turn what might otherwise be one-off purchases into more predictable, longer-term, and typically larger revenue streams. Microsoft, for example, now offers its Office 365 product through software-as-a-service subscriptions, as an alternative to purchasing an entirely new version of Office version every few years. Meanwhile Amazon offers its AWS product in a way that provides infrastructure as a service (IaaS) on a subscription basis. Thanks to increased digital connectivity and internet use, there has been a surge of data that can potentially provide value not just to companies but to society in general. Many companies are exploring innovative ways to unlock the value of this data in a responsible way by embedding trust, privacy, and security into their models. A company called Points Technology has for example used a confidential computing framework based on TEE (trusted execution environment) and other encryption technology to make data usable but not visible – in order to ensure privacy, security, and compliance when it comes to banking, government-led data-sharing initiatives, and marketing campaigns.

A carbon credit is a tradable permit or certificate that provides the holder of the credit the right to emit one ton of carbon dioxide or an equivalent of another greenhouse gas – it is essentially an offset for producers of such gases. The main goal for the creation of carbon credits is the reduction of emissions of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases from industrial activities to reduce the effects of global warming.

For Complete Market Insights, Access the Link: https://lnkd.in/ddS67BcP

Carbon credit is a mechanism for the minimization of greenhouse gas emissions. Governments or regulatory authorities set the caps on greenhouse gas emissions. For some companies, immediate reduction of emissions is not economically viable. Therefore, they can purchase carbon credits to comply with the emission cap. A carbon offset that is exchanged in the over-the-counter or voluntary market for credits is referred as Voluntary Emissions Reduction (VER). Whereas, emission units (or credits) created through a regulatory framework with the purpose of offsetting a project’s emissions is called as Certified Emissions Reduction (CER). The main difference between the two is that there is a third party certifying body that regulates the CER as opposed to the VER.

Latest Updates:

The Corporate Climate Finance Playbook

ESG Reporting and Data Management Software

Five reasons why companies should set science-based targets for nature

How to prepare a sustainability budget in 2023 by Business Companies

Sustainability action report – 2022 Deloitte survey findings show progress on ESG disclosure and preparedness

How business schools are exploring materiality in their own operations

Ten unsung digital and AI ideas shaping business

How to Develop Your Company’s ESG Policies

ESG: Do I need a software solution or a services partner? Or both?

Understanding the evolution of ESG

ESG Evolution and best Practices from Schnieder

Will ESG factors create or destroy value in your next deal? Six orange flags for dealmakers

How Your Company Can Advance Each of the SDGs

Responsible business and investment – rooted in universal principles – will be essential to achieving transformational change through the SDGs. For companies, successful implementation will strengthen the enabling environment for doing business and building markets around the world.

Below you will find links to important initiatives and resources of the UN Global Compact – and in some instances of other like-minded organizations – to guide companies and other stakeholders to action-oriented platforms and tools that support SDG implementation.

Unlocking Potential and Performance: Recognizing Education’s Position at the Core of ESG

Predictions for Business & Society in 2023

More than 330 businesses call on Heads of State to make nature assessment and disclosure mandatory at COP15.

What It Takes to Attract Private Investment to Climate Adaptation

A new approach to risk

Risk is fast-moving, uncertain and unpredictable. To succeed, organisations must be resilient, with the ability to adapt and emerge stronger from whatever disruption they face. We can work together to rethink your approach to risk, giving you greater insight into the challenges ahead so you can make confident decisions and uncover opportunities for growth.

Greenwashing: your guide to telling fact from fiction when it comes to corporate claims

AI: These are the biggest risks to businesses and how to manage them

Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) – impact on business

The private sector can (and should) lead the way on nature-positive

Sustainability strategy services

THE OPPORTUNITY TO RAISE THE QUALITY OF LIFE IS THE BIGGEST BUSINESS OPPORTUNITY GOING. – SDG

– Read more…..

Biodiversity Crisis is a Business Crisis

CLIMATE ACTION AT WORK – Read more

Not every job is a sustainability job, but you can bring. a sustainability lens into each and every job.

Private Sector Engagement for Quality TVET

The private sector has an important role to play in promoting quality TVET both as an employer and a training provider. Aligning existing TVET programmes to industry demand is a top priority as the world of work and training prepares for the post-COVID-19 ‘new normal’. Despite being such key players in TVET reform and implementation at the country level, companies and other development partners have limited venues for interaction and knowledge exchange at a global level. They are often working towards a similar goal – improving the quality of TVET –but have not been visible partners to each other.

Start your journey to net zero As an SME

Sustainability Leadership Survey 2022

sustainability leadership is increasingly being measured by evidence of action, impact, and above all the integration of sustainability into business strategy.

By 2050, 90% of land could become degraded. How can businesses help restore the resources they depend upon?

THE BUSINESS GUIDE TO CARBON ACCOUNTING

A guide to understanding carbon accounting, your organization’s environmental footprint, and how you can get started.

Planning to Decarbonize your Business – Here is what you need to consider

A Guide to Using Carbon Credits for Net-Zero Events

SDG INDUSTRY MATRIX – Climate Action Opportunities: An Industry Lens

Accelerating and Scaling Global Collective Impact – JOIN UN GLOBAL COMPACT

From climate change to equality, the world is not on track. Research predicts that we are likely to miss the goal of limiting global warming to 1.5°C unless immediate, rapid and large- scale climate action is taken. Exacerbated by the pandemic, the economic gender gap is also widening. Couple these challenges with almost 1 in 10 children subject to child labour, 7,500 people dying from unsafe and unhealthy working conditions every single day, and rampant inequality and racism worldwide and it’s clear we need bold action. Business has a critical role to play.

The pressure on companies is escalating

SDG COMPASS GUIDE

The steps

Our planet faces massive economic, social and environmental challenges. To combat these, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) define global priorities and aspirations for 2030. They represent an unprecedented opportunity to eliminate extreme poverty and put the world on a sustainable path.

ESG : creating a Sustained value for a Greener Planet

The ESG Leader’s Playbook:

ESG Program: Your Digital Hub to Operationalize ESG Reporting

Sustainability Management Software Empowers Sustainability Transformation

ESG Reporting 101: What You Need To Know

PROVING THE R O I Of ESG

Beyond the hype: what businesses can really expect from the metaverse in 2023

SUSTAINABILITY REPORTING POLICY: Global trends in disclosure as the ESG agenda goes mainstream

The Inadequacy of ESG: SEE a Fresh Approach

A Climate Disclosure Framework for SME’s

6 Reasons Spreadsheets Don’t Cut It for ESG Management

Start of a global quest -Have we perhaps overlooked something?

PwC’s “Climate Excellence tool” for climate scenario analyses

The Future Of Nature And Business

A sustainable future requires business action for the SDGs

State of Green Business 2023

The “S” in ESG a Business Imperative

Climate Challenge = Climate Opportunity – Strategy plus Business from PWC

Winning today’s race while running tomorrow’s

Critical Business action for Climate Change Adaptation

BOLD CLIMATE POLICY DRIVES DECISIVE BUSINESS ACTION -The transition to a net-zero economy has begun. It’s achievable and brings significant benefits.

The Degrowth Opportunity – Reshaping business for a needs-satisfying, resource wise economy

Critical Business Actions for Climate Change Adaptation

A digital transformation in global ESG reporting is needed

Pushing back, moving forward: understanding the evolution of ESG

Nine tough questions, under three themes, that CEOs need to tackle.

ESG is under fire and education may save it

ESG Playbook Solutions

ESG Is Going to Have a Rocky 2023. Sustainability Will Be Just Fine.

How to strengthen sustainability agenda of a Brand

ESG Compass: A self-assessment tool to help you understand your business’ ESG maturity.

Click here to fill the Survey form …

2023 Net Positive Employee Barometer

Environmental Sustainability for SMEs

Ripple Effects: What Recent ESG Policy Developments in the EU Mean for the Rest of the World

How Generative AI can build your Organizations ESG Roadmap

Starting a CSR Department in Your Company? Here’s Your Ultimate Guide

Climate Disclosure Rule: Eight Myths Debunked

Read more….

The environment is changing, but is your business?

Governments, companies and individuals have to come together to address the urgent climate crisis. Policymakers, business leaders and the global workforce have a shared opportunity and responsibility.

Achieving our climate targets is a monumental task and it is going to take a whole-of-economy effort to make it happen. That means we need a transformation in the skills and jobs people have if we’re going to get there.

Green skills are the core of the green transition and harnessing the shift of talent. Through a targeted approach, we can progressively shift towards these greener jobs, using skills to identify jobs with the highest ability to turn sectors and countries green. We need more opportunities for those with green skills, we have to upskill workers who currently lack those skills, and we need to ensure green skills are hardwired.

|

Adapting to Evolving ESG Requirements |

|

In response to growing concerns among their employees customers, investors, and impacted communities, many firms are making themselves accountable for their environmental, social and governance (ESG) practices. How can businesses ensure future success by adopting the best ESG practices? |

The ABC of ESG

ESG stands for Environmental, Social and Governance. Collectively, these cover a broad range of non-financial issues that are increasingly regarded as sources of both financial risk and opportunity. In this article, we’ll delve into the origins and implications of ESG.

The Origins and Growth of ESG

The original use of the term ESG dates back to 2004, when the then-United Nations Secretary-General Kofi Annan invited 55 CEOs of major financial institutions to participate in an international project to integrate ESG into capital markets. That group produced a study in 2005 entitled ‘Who Cares Wins’, which set out the business case for embedding ESG factors into investment decisions, thereby improving the sustainability of markets and leading to better outcomes for society.

Since those early days, ESG investing has grown significantly. One indicator is the growth in the number of signatories and assets covered by the Principles for Responsible Investment Initiative (PRI) (Figure 1). Launched in 2006, signatories commit to incorporate ESG considerations into their businesses and investment processes.

Figure 1 PRI growth 2006 – 2020

Source: https://www.unpri.org/pri/about-the-pri

So What Counts as Being Part of ESG?

- The Environmental pillar refers to issues related to the natural world and includes aspects such as greenhouse gas (GHG) and non-GHG emissions; renewable/non-renewable energy generation and usage; biodiversity; land use; material resource use; water management and waste.

- The Social pillar refers to issues related to the lives of humans, such as human rights, modern slavery, child labor, working conditions, and employee relations.

- The Governance pillar captures the decision-making factors affecting a business, such as the gender and ethnic diversity of board composition, executive pay, bribery and corruption policies, political lobbying and donations, and tax strategy/transparency.

Where Does Climate Fit In?

The risks and opportunities from a changing climate most obviously fall in the environment pillar, although social (e.g. support for a ‘just’ transition to a low carbon economy) and governance issues (e.g. how well executive incentives align to climate outcomes) may also be relevant.

Investors’ Fiduciary Duties

An area of long-standing debate – particularly for asset managers – has been the extent to which taking account of ESG issues is compatible with their ‘fiduciary duty’, that is, the duty to work in the best interests of one’s clients. If fiduciary duty is interpreted as the maximization of shareholder value, it provides a reason to ignore broader environmental or social impacts, which might be costly to improve or rectify.

A UNEPFI sponsored report published in 2005 made it clear that there were no legal barriers in taking ESG considerations into account. Indeed, as they noted ‘…there is a body of credible evidence demonstrating that such considerations often have a role to play in the proper analysis of investment value’. While that report was helpful, it didn’t manage to end the debate and over the years this has been a constant refrain. Extensive work by the PRI and UNEP FI on this issue culminated in a 2015 report which stated that ‘Failing to consider long-term investment value drivers, which include environmental, social and governance issues, in investment practice is a failure of fiduciary duty.’ (Emphasis added).

Beyond Asset Management

ESG issues are not just pertinent to asset management and asset owners. Initiatives similar to the PRI have been launched more recently for Insurance and Banking. The spirit of all these initiatives is that ESG issues need to be considered as potential sources of risk as they can impact a firm at any point.

Indeed, today’s 24-hour news cycles and social media make the reputational impacts of ESG transgressions particularly difficult to manage.

ESG Fragmentation

That said, judging which ESG issues are financially relevant and material for a particular firm can be difficult. Because ESG data and metrics have not traditionally been part of the mandatory financial reporting frameworks, a plethora of different approaches have grown up, making it challenging to compare across firms. And although there are efforts to introduce a globally more consistent approach to sustainability reporting, the landscape at the moment is confusing and fragmented. Indeed, as a 2020 OECD report noted, there is now an entire ESG financial ecosystem, from issuers to end investors, ratings providers, firms that construct ESG indices, standard setters, and disclosure organizations, and they could all be using different definitions and metrics (Figure 2).

Figure 2 ESG financial ecosystem

Source: https://www.oecd.org/finance/ESG-Investing-Practices-Progress-Challenges.pdf

Work is underway by the five leading framework and standard-setting organizations – CDP, Climate Disclosure Standards Board (CDSB), Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC) and the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) – to work towards a comprehensive corporate reporting system that includes both financial accounting and sustainability disclosures as outlined in their shared visiondocument in September 2020. But that will take time.

In the meanwhile, care is needed. Self-reported ESG metrics by firms will tend to put a gloss on issues of interest from a risk perspective. ESG ‘scores’ of companies from different providers are not well correlated, reflecting differences in proprietary methodologies, weighting schemes, and materiality assessments. Indeed, it is questionable if it even makes sense to weigh together the differing aspects of the three E, S, and G pillars to get to an aggregate score. (For an interesting discussion on this and other topics, listen to a recent GARP Climate risk podcast).

But even if you restrict yourself to just looking at the Environmental pillar, a recent OECD report highlights how little alignment there is between E scores from key rating providers (Bloomberg, MSCI, and Thomson Reuters) and climate risk indicators such as carbon dioxide emissions, and waste and water metrics. As they put it, “the E of ESG investing – in its current form – may not be the most effective tool for investors who wish to use it to align portfolios with climate transition to low-carbon economies”. Definitely food for thought for anyone wanting to use ESG scores as a shortcut to investing in climate-friendly investments.

Environment, Social Governance (ESG) – A Global Issue

Companies are expanding the metrics they use to define success well beyond profit and sales. In response to growing concerns among their employees, customers, investors, and impacted communities, many firms are making themselves accountable for their Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) practices. Mainstream investors once considered such measures “non-financial,” but have come to understand both related risks and opportunities – and are demanding more related data. The amount of ESG information being made available by rating agencies, technology firms, and auditing and consulting firms has exploded as a result, and efforts are afoot to bring more coherence and consistency to it through standards and regulation.

ESG Regulation and Policy Making

Without proper Environmental, Social and Governance regulation potentially harmful ‘greenwashing’ efforts may flourish

The market for sustainable investing has expanded rapidly. Both financial and non-financial firms have begun making claims about the environmental and social performance of the investments they offer, in hopes of tapping into a growing trend. For non-financial firms like technology companies their claims may take the form of sustainability reports designed to attract certain equity and debt investors, while financial firms have developed product labels like “green bond” and “sustainable growth fund” with the same goal in mind. If left unregulated, however, the potential for rampant “greenwashing” presents a serious challenge for the ESG capital market. Firms and financial actors have an incentive to make their activities appear green, without going to the trouble of carefully measuring, auditing, and improving actual ESG performance. If greenwashing firms are rewarded by the unsuspecting, it could further exacerbate bad behaviour. And, when deceptions inevitably come to light, the resulting decline in trust could cut general demand for ESG performance, erode the incentives for good behaviour, and even collapse the overall market. To be sustainable, the ESG-informed capital market therefore needs more ways to reliably and systematically validate ESG claims.

This validation can be derived from industry self-monitoring and auditing, non-governmental organizations, government regulation, or technologies like blockchain. The first significant efforts to regulate ESG were made through non-governmental organizations like the Global Reporting Initiative, the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board, and the Financial Stability Board’s Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures, which define standards for the reporting of non-financial ESG information. The issue with such voluntary standards, however, is adverse selection – only certain firms have an incentive to accurately report and audit, while others are content to avoid scrutiny. In 2020, governmental regulations began to develop that fully cover the market, like the EU taxonomy to define and oversee differing levels of rigour in the ESG investing market. The US Securities and Exchange Commission has also considered required disclosures. The need for convergence among non-governmental and governmental standards has pointed to the importance of harmonizing institutions like the World Economic Forum’s Stakeholder Capitalism Metrics Initiative, The Value Reporting Foundation, and the Impact Management Project. Perhaps the most important of these is the International Sustainability Standards Board, created by the International Financial Reporting Standards Foundation and launched at the COP26 climate summit in Glasgow. This new entity is the result of a merger between the Climate Disclosure Standards Board and the Value Reporting Foundation, which houses the Integrated Reporting Framework and the SASB Standards.

ESG Investment Integration

Portfolios may outperform by tilting towards companies with high Environmental, Social and Governance scores

ESG investment integration means using Environmental, Social and Governance performance data to construct a portfolio – to both maximize returns and address ethical concerns. Asset managers are increasingly purchasing data from ESG rating agencies and integrating that with other available corporate information to guide investment decisions. From an ethical investing perspective, ESG information enables a finer-grained approach than simply screening out industries like weapons, addictive substances, fossil fuels, or private prisons. By using ESG data, for example, it is possible to invest in fossil fuels using a “best in class” approach that excludes companies above a certain level of carbon intensity, or to only own tobacco companies with responsible marketing practices. Unfortunately, this exclusionary approach to publicly-traded equities has had only weak and indirect impacts on firm behaviour. ESG integration may therefore fit best within a “virtue ethics” perspective, where investors refuse to benefit from things they don’t believe in. One alternative is to take a “consequentialist ethics,” or impact perspective – where investors use their money to try to change the world for the better. However, to have that kind of influence on corporate behaviour, it will likely require active and engaged ownership.

The primary benefit of ESG integration may be financial – at least, in situations where ESG variables are predictive of future financial performance. While scandals related to harsh labour conditions in supply chains, corruption schemes, and environmental damage can affect a company’s reputation and stock price, they may also be anticipated by low ESG scores. Meanwhile a company’s greenhouse gas emissions may point to future costs, as governments increasingly move to put a price on carbon. In aggregate, ESG appears to have a neutral-to-positive impact on financial performance; as a result, it may be possible for portfolios to outperform by tilting towards companies with higher ESG scores. This has driven a meteoric rise in ESG investing, though there are two main issues that may impede further progress. The first is the high level of noise within ESG data, which tends to reduce its correlation to financial performance (though new techniques to address this might strengthen the signal). The second is the added capability needed within investment firms, given the complexities of ESG data and the variety of values and preferences among clients. Building related capacity will likely require the joint efforts of academia and industry.

ESG Ratings and Rankings

Useful Environmental, Social and Governance performance measurement relies on a shared definition of ESG